The Ultimate Guide to Maize: Everything You Need to Know About This Ancient Wonder Grain

Discover everything about maize—its history, health benefits, types, cultivation, and uses. The ultimate guide to this ancient grain and global food staple.

Prempal

7/21/20257 min read

The Ultimate Guide to Maize: Everything You Need to Know About This Ancient Wonder Grain

What is Maize?

Maize (Zea mays) is a tall annual cereal grass that produces large elongated ears of starchy seeds, commonly known as corn in North America. Originally domesticated from wild teosinte by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico approximately 9,000-10,000 years ago, maize has become one of the world's most important cereal grains alongside wheat, barley, and rice. The domesticated crop now surpasses wheat and rice in total global production.

The maize plant features a stout, erect stem reaching heights of approximately 3 meters. Its large narrow leaves have wavy margins and are arranged alternately on opposite sides of the stem. Male inflorescences (tassels) develop at the top of the stem, producing pollen, while female inflorescences (ears) form between the stem and leaves. When fertilized, these ears yield grain kernels or seeds that can be yellow, white, red, blue, purple, or black [31].

Modern maize cultivation spans from 58° N latitude in Canada and Russia to 40° S latitude in South America. In 2020, global maize production reached 1.1 billion tons, making it the most widely produced grain by weight in the world. A maize crop matures somewhere globally nearly every month of the year.

The major chemical component of the maize kernel is starch, comprising 72-73% of kernel weight. Additionally, maize contains 8-11% protein, 3-18% oil (genetically controlled), and approximately 1.3% mineral content. The grain also provides dietary fiber and essential vitamins, including B vitamins (thiamin, niacin, pantothenic acid, folate), vitamin A (in yellow varieties), and vitamin E.

Maize is exceptionally versatile in its applications. Beyond human consumption as whole kernels, flour, meal, or oil, it serves as livestock feed, a source for biofuels like ethanol, and a raw material for various industrial products including starch, sweeteners, beverages, plastics, and other chemical feedstocks. Maize varieties include dent corn, flint corn, flour corn, sweet corn, popcorn, and waxy corn, each with specific characteristics and uses [22].

Throughout history, maize has held cultural significance for many indigenous peoples of the Americas. The Taíno people referred to it as "Mahiz," meaning "source of life". It formed part of the "Three Sisters" agricultural system alongside beans and squash in traditional Native American cultivation practices [22].

Types of Maize

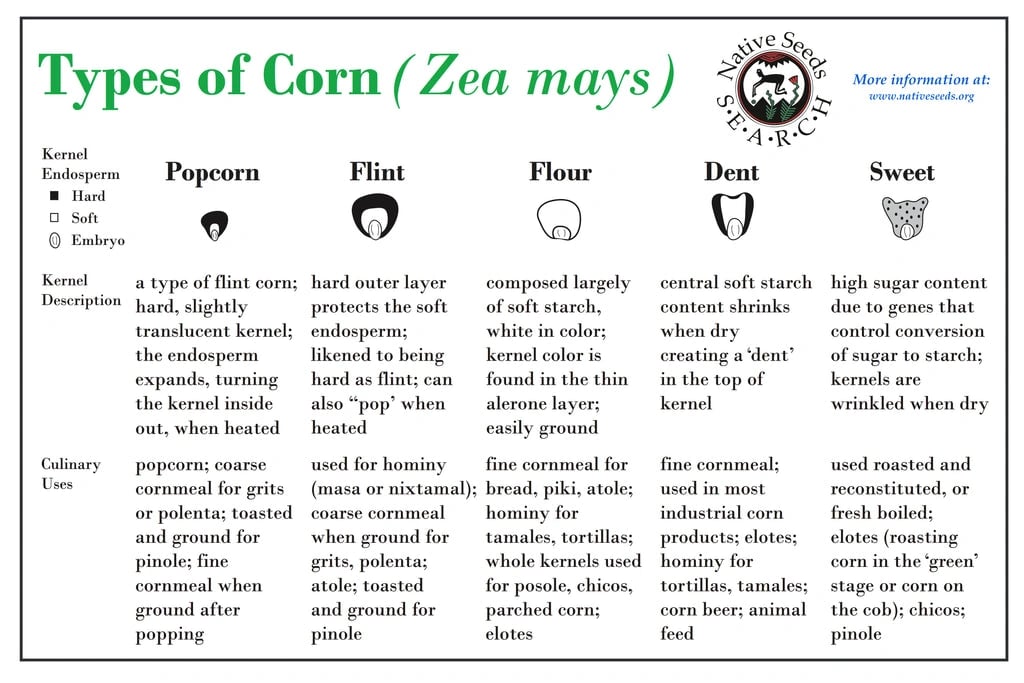

Image Source: Native-Seeds-Search

Maize exists in several distinct varieties, each with unique characteristics and specific uses. These types differ primarily in their kernel structure, starch composition, and cultivation purposes.

Field corn

Field corn constitutes more than 99% of all corn grown in Nebraska and is the predominant type cultivated in the United States. Unlike varieties meant for direct human consumption, field corn is harvested when hard and dry, featuring a distinctive dent that forms as the kernel dries. Field corn serves primarily as livestock feed and a raw material for ethanol production. Furthermore, only part of the kernel is used for ethanol (the starch), with the remaining protein and fat components utilized to create distillers grains for animal feed. This variety requires processing before human consumption, typically being milled into products like corn syrup, corn flakes, chips, starch, or flour.

Sweet corn

Sweet corn is the variety familiar to most consumers as fresh corn-on-the-cob, canned corn, or frozen corn. Unlike field corn, sweet corn is harvested early while the kernels remain young, plump, and moist at peak flavor. Sweet corn contains elevated natural sugar levels, hence its name. Modern breeding has developed various sweetness types classified by genetic traits: standard sugary (su) types grown mostly for processing; sugary enhanced (se) types known for creamy texture and local markets; and supersweet (sh2) varieties with higher sugar content and longer shelf life for shipping.

Popcorn

Popcorn is a specialized type of flint corn with a hard exterior and small amount of water inside each kernel. When heated, this moisture expands until the kernel bursts open, creating a light, airy snack. Americans consume approximately 16 billion quarts of popped popcorn annually—51 quarts per person. Nebraska leads U.S. production, harvesting about 300 million pounds on roughly 67,000 acres. Commercial popcorn varieties are categorized as either "rice" type (long kernels pointed at both ends) or "pearl" type (rounded top kernels), with commercial production dominated by white and yellow colors.

Flint corn

Flint corn features a hard outer layer that protects the soft endosperm inside each kernel. This hardness, likened to flint, gives the variety its name. Typically multi-colored, flint corn has a long history of cultivation by Native Americans, with research identifying its cultivation beginning around 1000 BCE in the southwestern USA. Due to its low water content, flint corn offers superior freezing resistance compared to other vegetables. It serves as the preferred type for making hominy and is often used decoratively during autumn holidays.

Dent corn

Dent corn, sometimes called grain corn, receives its name from the small indentation that forms at the crown of each kernel as it dries. It contains high soft starch content with vitreous, horny endosperm at the sides and back. Most corn grown in the U.S. Corn Belt is yellow dent corn. This variety serves as the primary ingredient in livestock feed and ethanol production. Additionally, dent corn provides the base for cornmeal flour used in cornbread, corn chips, tortillas, and taco shells.

Waxy corn

Waxy corn starch consists almost entirely of amylopectin molecules, giving it distinctive properties. Despite its name, waxy corn contains no actual wax—the term comes from its endosperm's shiny, wax-like appearance when cut. Originally discovered in China in the early 1900s, waxy corn was developed into a commercial crop in the United States during the 1940s. Given its unique starch composition, waxy corn is particularly valuable for food processing, especially in products requiring freeze-thaw stability. Approximately 1.5% of corn processed by wet milling in the United States is waxy type.

How Maize is Used Around the World

Cultivated across 166 countries in every agro-ecological region from arid to tropical zones, maize serves as a cornerstone of global agriculture and industry. Internationally grown on 184 million hectares with annual production reaching 1016 million tons, this versatile crop ranks third worldwide after rice and wheat.Write your text here...

Food and cooking

Globally, maize constitutes 13% of direct human food consumption from dry grain. Consumption patterns vary significantly by region, with eastern and southern Africa utilizing 66% of production for food compared to the global average of 43% in lower-income countries. In countries like Lesotho, Malawi, and Zambia, per capita consumption exceeds 100 kg annually. Processing methods range from traditional milling for porridges and gruels to nixtamalization for tortillas and masa in Latin America. In India, makai ka atta (maize flour) features prominently in regional dishes such as Punjabi rotis, Rajasthani tikkar, and Gujarati dhokla.

Animal feed

Approximately 61% of global maize production serves as livestock feed. This percentage rises to nearly 65% worldwide for poultry, cattle, and pig nutrition. In India specifically, poultry feed incorporates 60-65% maize, consuming roughly 21 million tons annually. Beyond grain, animals benefit from maize stover (post-harvest plant material), silage, and industrial by-products like distillers' dried grains with solubles (DDGS). The digestibility of maize fodder exceeds that of sorghum, bajra, and other non-leguminous forage crops.Write your text here...

Biofuel and ethanol

Maize serves as a principal feedstock for biofuel production, yielding approximately 380 liters of ethanol per ton. In 2023-24, Indian distilleries produced 286.54 crore liters of ethanol from 7.5 million tons of maize. Ethanol blending with gasoline has gained prominence because of its higher octane number (108 vs. 95-98) and superior heat vaporization compared to gasoline components. Furthermore, the ethanol production process generates valuable by-products, with one ton of DDGS substituting 1.2 tons of maize grain in animal feed.

Industrial products

Maize serves as a raw material for thousands of industrial products. Cornstarch functions as a key ingredient in pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, textiles, packaging, and paper industries. Moreover, bioplastics derived from maize starch produce biodegradable alternatives for disposable items. High-fructose corn syrup, developed in the mid-1970s, revolutionized food sweeteners. Additional industrial applications include corn oil extraction (2.8% by weight), adhesives, films, and gums.Write your text here...

Maize and malt in beverages

Throughout history, maize has played a significant role in beverage production. In ancient Andean cultures, chicha (corn beer) dates back to pre-Incan civilizations. Modern applications include both alcoholic and non-alcoholic options. Maize serves as an adjuvant in European brewing, reducing production costs by approximately 8% when used at 30% concentration. Researchers have successfully produced beer from 100% corn malt, yielding a clear, light yellow beverage with good foam stability and flavor similar to traditional beer. Non-alcoholic maize malt beverages comparable to commercial brands have been developed through optimized malting and saccharification processes.

Maize in Culture and Modern Science

Throughout human history, maize has transcended its role as a mere food crop to become a cultural cornerstone and scientific marvel across civilizations.

Maize in ancient civilizations

The Maya civilization regarded maize as sacred, believing humans were created from maize dough by the gods according to the Popol Vuh, their creation story. Two primary maize deities featured prominently in Mayan theology: the Tonsured Maize God, whose shaven head represented a corn cob with a small hair crest symbolizing the tassel, and the Foliated Maize God, representing young, green maize. Similarly, Aztec civilization venerated several maize deities, including Chicomecóatl (goddess of mature maize) and Xilonen (goddess of young maize). Nixtamalization, the process of treating maize kernels with limewater, originated in Mesoamerica, improving nutritional value by freeing niacin and preventing pellagra.

Genetic research and GMOs

Barbara McClintock used maize to validate her transposon theory of "jumping genes," earning the 1983 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. As a testament to its scientific importance, maize remains a vital model organism for genetics and developmental biology. In 2008, scientists completed sequencing the maize genome, revealing 32,540 genes with 85% of the genome composed of transposons. Currently, genetically modified maize constitutes a significant portion of global production—86% of the USA maize crop was genetically modified in 2010, whereas 32% of worldwide maize was GM in 2011.

Maize in art and symbolism

Maize imagery appears prominently in architecture and art worldwide. In the United States Capitol building, maize ears are carved into column capitals. The Corn Palace in Mitchell, South Dakota features annual murals created from colored maize cobs. The Field of Corn sculpture in Dublin, Ohio displays hundreds of concrete maize ears in a grassy field. Even currency features maize—the Croatian 1 lipa coin, minted since 1993, depicts a maize stalk with two ripe ears on its reverse. Historically, maize kernels sometimes symbolized cowardice, as exemplified when anti-Allende protestors threw maize at military barracks before the 1973 Chilean coup d'état.